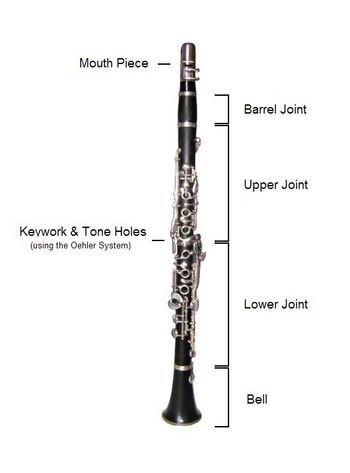

Two soprano clarinets: a Bb clarinet (left) and an A clarinet (right, with no mouthpiece).

These use the Oehler system of keywork.

The clarinet is a musical instrument in the woodwind family. The name derives from adding the suffix

-et meaning little to the Italian word clarino meaning a particular trumpet,

as the first clarinets had a strident tone similar to that of a trumpet. The instrument has an approximately

cylindrical bore, and uses a reed.

Clarinets actually comprise a family of instruments of differing sizes and pitches. It is the largest such

instrument family, with more than two dozen types. Of these many are rare or obsolete, and music written for

them is usually played on one of the more common size instruments. The unmodified word clarinet usually

refers to the B flat soprano, by far the most common clarinet.

A person who plays the clarinet is called a clarinetist, sometimes spelled "clarinettist".

Characteristics of the instrument

Tone

The clarinet has a distinctive timbre, resulting from the shape of the cylindrical bore, whose characteristics

vary between its three main registers: the chalumeau (low), clarion or clarino (middle), and altissimo (high).

It has a very wide compass, which is showcased in chamber, orchestral, and wind band writing. The tone quality

varies greatly with the musician, the music, the style of clarinet, the reed, and humidity. The German (Oehler)

clarinet generally has a darker tone quality than the French (Boehm) system. In contrast, the French clarinet

typically has a lighter, brighter tone quality. The differences in instruments and geographical isolation of

players in different nations led to the development, from the last part of the 18th century on, of several

different schools of clarinet playing. The most prominent of these schools were the German/Viennese traditions

and the French school, centered around the clarinettists of the Conservatoire National Superieur de Musique de

Paris. Increasingly, through the proliferation of recording technology and the internet, examples of many

different styles of clarinet playing are available to developing clarinettists today. This has led to decreased

homogeneity of styles of clarinet playing. The modern clarinetist has an eclectic palette of "acceptable" tone

qualities to choose from, especially when working with an open-minded teacher.

The A clarinet sound is a little darker, richer, and less brilliant than that of the more common B flat clarinet,

though the difference is relatively small. The tone of the E flat clarinet is quite a bit brighter than any other

member of the widely-used clarinet family and is known for its distinctive ability to cut through even loud

orchestral textures; this effect was utilized by such 20th century composers as Mahler, Copland, Shostakovich,

and Stravinsky.

The bass clarinet has a characteristically deep, mellow sound.

Range

Written range of soprano clarinets.

The bottom of the clarinet's written range is defined by the keywork on each particular instrument; there are

standard keywork schemes with some variability. The actual lowest concert pitch depends on the transposition

of the instrument in question; in the case of the B flat, the concert pitch is a whole tone lower than the written

pitch. Nearly all soprano and piccolo clarinets have keywork enabling them to play the E below middle C as their

lowest written note. Alto and bass clarinets have an extra key to allow a low Eb. Modern professional-quality

bass clarinets generally have additional keywork to low C. Among the less commonly encountered members of the

clarinet family, contra-alto and contrabass clarinets may have keywork to low Eb, D, or C; the basset clarinet

and basset horn generally go to low C.

Defining the top end of a clarinet's range is difficult, since many advanced players can produce notes well

above the highest notes commonly found in method books. The "high G" two octaves plus a perfect fifth above

middle C is routinely encountered in advanced material and in the standard literature through the nineteenth

century. The C above that is attainable by most advanced players and is shown on many fingering charts. Many

professional players are able to extend the range even higher.

The range of a clarinet can be divided into three distinctive registers. The lowest notes, up to the written

B flat above middle C, is known as the 'chalumeau register' (named after the instrument that was the clarinet's

immediate ancestor), of which the top four notes or so are known as the 'throat tones'. Producing a blended

tone with the surrounding registers takes much skill and practice. The middle register is termed the 'clarion'

register and spans just over an octave (from written B above middle C, to the C two octaves above middle C).

The top or 'altissimo' register consists of the notes from the written C# two octaves above middle C and up.

Construction and acoustics

The Construction of a Clarinet

Professional clarinets are usually made from African hardwood, often grenadilla, (rarely) Honduran rosewood

and sometimes even cocobolo. Historically other woods, notably boxwood, were used. One major manufacturer makes

professional clarinets from a composite mixture of plastic resin and wood chips - such instruments are less

affected by humidity, but are heavier than the equivalent wood instrument. Student instruments are sometimes

made of composite or plastic resin, commonly "resonite", an ABS resin. Metal soprano clarinets were popular in

the early twentieth century, until plastic instruments supplanted them; metal construction is still used for

some contra-alto and contrabass clarinets. Mouthpieces are generally made of ebonite, although some inexpensive

mouthpieces may be made of plastic. The instrument uses a single reed made from the cane of arundo donax, a type

of grass. Reeds may also be manufactured from synthetic materials. The ligature fastens the reed to the mouthpiece.

When air is blown through the opening between the reed and the mouthpiece facing, the reed vibrates and produces

the instrument's sound.

Clarinetists used to make their own reeds. Now most buy manufactured reeds, but many players make adjustments to

these reeds to improve playability. Clarinet reeds come in varying "strengths" generally described from "soft" to

"hard." The most common scale is a 1-5 system with most manufacturers having slight differences in their own systems.

It is important to note that there is no standardized system of designating reed strength. Beginning clarinetists are

often encouraged to use softer reeds, usually a 2 to 2 1/2. Jazz clarinetists often remain on softer reeds, as they are

easy for bending pitch. Most classical musicians work towards harder reed strengths as their embouchures strengthen.

The benefit of a harder reed is a sturdy, round tone. The major manufacturers of clarinet reeds include the Vandoren

company (France), Gonzalez and Zonda (both manufactured from the same cane in Argentina), Legere, Mitchell Lurie and

many others. However it should be noted that the strength of the reed is only one factor in the player's set-up; the

"tip-opening" and "lay" of the mouthpiece are other critical factors.

The body is equipped with seven tone holes (six front, one back) and a complicated set of keys which allow

every note of the chromatic scale to be produced. The most common system of keys was named the Boehm System by its

designer Hyacinthe Klose in honour of the flute designer Theobald Boehm, but is not the same as the Boehm System used

on flutes. The other main system of keys is called the Oehler system and is used mostly in Germany and Austria.

Related is the Albert system used by some jazz, klezmer, and eastern European folk musicians. The Albert and Oehler

systems are both based on the earlier Muller system.

The hollow bore inside the instrument has a basically cylindrical shape, being roughly the same diameter for most of

the length of the tube. There is a subtle hourglass shape, with its thinnest part at the junction between the upper

and lower joint. This hourglass figure is not visible to the naked eye, but helps in the resonance of the sound. The

diameter of the bore affects characteristics such as the stability of the pitch of a given note, or, conversely, the

ability with which a note can be 'bent' in the manner required in jazz and other styles of music. The bell is at the

bottom of the instrument and flares out to improve the tone of the lowest notes.

A clarinetist moves between registers through use of the register key, or speaker key. The fixed reed and fairly

uniform diameter of the clarinet give the instrument the configuration of a cylindrical stopped pipe in which the

register key, when pressed, causes the clarinet to produce the note a twelfth higher, corresponding to the third

harmonic. The clarinet is therefore said to overblow at the twelfth. (By contrast, nearly all other woodwind

instruments overblow at the octave, or do not overblow at all; the rackett is the next most common Western instrument

that overblows at the twelfth like the clarinet.) A clarinet must therefore have holes and keys for nineteen notes

(an octave and a half, from bottom E to B flat) in its lowest register to play a chromatic scale. This fact at once

explains the clarinet's great range and its complex fingering system. The fifth and seventh harmonics are also

available to skilled players, sounding a further sixth and fourth (actually a very flat diminished fifth) higher

respectively.

The highest notes on a clarinet can have a piercing quality and can be difficult to tune precisely. Different

individual instruments can be expected to play differently in this respect. This becomes critical if a number of

instruments are required to play a high part in unison. Fortunately for audiences, disciplined players can use a

variety of fingerings to introduce slight variations into the pitch of these higher notes. It is also common for

high melody parts to be split into close harmony to avoid this issue.

The parts that make up a clarinet are as follows (description follows the illustration from right to left):

A concert Bb Clarinet (Boehm system)

-

The reed is attached to the mouthpiece by the ligature and the top half-inch or so of

this assembly is held in the player's mouth. The formation of the mouth around the mouthpiece and reed is

called the embouchure. The reed is on the underside of the mouthpiece pressing against the player's

bottom lip, while the top teeth normally contact the top of the mouthpiece (some players roll the upper lip

under the top teeth to form what is called a 'double-lip' embouchure). Adjustments in the strength and

configuration of the embouchure change the tone and intonation (tuning).

-

Next is the short barrel; this part of the instrument may be extended in order to fine-tune the

clarinet. As the pitch of the clarinet is fairly temperature sensitive some instruments have interchangeable

barrels whose lengths vary very slightly. Additional compensation for pitch variation and tuning can be made

by increasing the length of the instrument by pulling out the barrel. Some performers employ a single,

synthetic barrel with a thumbwheel that enables the barrel length to be altered on the fly.

-

The main body of the clarinet is divided (in most soprano clarinets, and some harmony clarinets) into the

upper joint whose holes and most keys are operated by the left hand, and the lower joint with

holes and most keys operated by the right hand. The left thumb operates both a tone hole and the

register key. The cluster of keys in the middle of the illustration are known as the trill keys

and are operated by the right hand. These give the player alternative fingerings which make it easy to play

ornaments and trills that would otherwise be awkward. The entire weight of the smaller clarinets is supported

by the right thumb behind the lower joint on what is misleadingly called the thumb-rest. Alto and larger

clarinets are supported with a neck strap or a floor peg.

-

Finally, the flared end is known as the bell. Contrary to popular belief, the bell does not amplify

the sound; rather, it improves the uniformity of the instrument's tone for the lowest notes in each register.

For the other notes the sound is produced almost entirely at the tone holes and the bell is irrelevant. As a

result, when playing to a microphone, the best tone can be recorded by placing the microphone not at the bell

but a little way from the finger-holes of the instrument. This relates to the position of the instrument when

playing to an audience: pointing down at the floor, except in the most vibrant parts of certain styles of music

and when called for specifically by the composer in the music (for example, in the music of Gustav Mahler).

Usage and repertoire of the clarinet

Clarinets have a very wide compass, which is showcased in chamber, orchestral, and wind band writing. Additionally,

improvements made to the fingering systems of the clarinet over time have enabled the instrument to be very agile;

there are few restrictions to what it is able to play.

Classical music

In classical music, clarinets are part of standard orchestral instrumentation, which frequently includes two

clarinetists playing individual parts - each player usually equipped with a pair of standard clarinets in B flat and A.

Clarinet sections grew larger during the 19th century, employing a third clarinetist or a bass clarinet. In the

20th century, composers such as Igor Stravinsky, Richard Strauss and Olivier Messiaen enlarged the clarinet section

on occasion to up to nine players, employing many different clarinets including the E flat or D soprano clarinets,

bassett horn, bass clarinet and/or contrabass clarinet. This practice of using a variety of clarinets to achieve

colouristic variety was common in 20th century music and continues today. However, many clarinetists and conductors

prefer to play parts originally written for obscure instruments such as the C or D clarinets on B flat or E flat

clarinets, which are of better quality and more prevalent and accessible.

The clarinet is widely used as a solo instrument. The relatively late evolution of the clarinet (when compared to

other orchestral woodwinds) has left a considerable amount of solo repertoire from the Classical, Romantic and

Modern periods but few works from the Baroque era. A number of clarinet concertos have been written to showcase

the instrument, with the concerti by Mozart, Copland and Weber being particularly well known.

Many works of chamber music have also been written for the clarinet. Particularly common combinations are:

- Clarinet and piano (including clarinet sonatas)

- Clarinet, piano and another instrument (for example, string instrument or voice)

- Clarinet Quintet, generally made up of a clarinet plus a string quartet,

- Wind Quintet, consists of flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, and horn.

- Trio d'Anches, or Trio of Reeds consists of oboe, clarinet, and bassoon.

- Wind Octet, consists of pairs of oboes, clarinets, bassoons, and horns.

- Clarinet, violin, piano

Concert bands

In wind bands, clarinets are a particularly central part of the instrumentation, occupying the same space (and

often playing the same parts) in bands that the strings do in orchestras. Bands usually include several B flat clarinets,

divided into sections each consisting of 2-3 clarinetists playing the same part. There is almost always an E flat clarinet

part and a bass clarinet part, usually doubled. Alto, contra-alto, and contrabass clarinets are sometimes used as well,

and very rarely a piccolo A flat clarinet.

Jazz

Dr Michael White (front right) plays clarinet at a jazz funeral in Treme, New Orleans, Louisiana.

The clarinet was a central instrument in early jazz starting in the 1910s and remaining popular through the big band

era into the 1940s. Larry Shields, Ted Lewis, Jimmie Noone and Sidney Bechet were influential in early jazz. The B flat

soprano was the most common, but a few early jazz musicians such as Louis Nelson Deslile and Alcide Nunez preferred

the C soprano, and many New Orleans jazz brass bands have used E flat soprano.

Swing clarinetists such as Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw, and Woody Herman led successful and popular big bands and

smaller groups from the 1930s onward.

With the decline of big bands' popularity in the late 1940s, the clarinet faded from its prominent position in jazz,

though a few players (Buddy DeFranco, Eric Dolphy, Jimmy Giuffre, Perry Robinson, and others) used clarinet in bebop

and free jazz. The instrument has seen something of a resurgence since the 1980s, with Eddie Daniels, Don Byron,

and others playing the clarinet in more contemporary contexts. The instrument remains common in Dixieland music;

Pete Fountain is one of the best known performers in this genre. Filmmaker Woody Allen is one notable clarinet

enthusiast, regularly playing New Orleans-style jazz in New York.

Klezmer

Clarinets also feature prominently in much Klezmer music, which requires a very distinctive style of playing. This

folk genre makes much use of quarter-tones, making a different embouchure (mouth position) necessary.

Groups of clarinets

Groups of clarinets playing together have become increasingly popular among clarinet enthusiasts in recent years.

Common forms are:

- clarinet choir, which features a large number of clarinets playing together, usually involving a range of

different members of the clarinet family. The homogeneity of tone across the different members of the clarinet

family produces an effect with some similarities to a human choir.

- clarinet quartet, for which three B flat sopranos and one B flat bass is a particularly common combination

Clarinet choirs and quartets often play arrangements of both classical and popular music, in addition to a body

of literature specially written for a combination of clarinets by composers such as Arnold Cooke, Alfred Uhl,

Lucien Caillet and Vaclav Nehlybel.

Extended family of clarinets

Clarinets other than the standard B flat and A clarinets are sometimes known as harmony clarinets. However, there

are many differently-pitched clarinet types, some of which are very rare. They may be grouped into sub-families,

but grouping and terminology vary; the following grouping is intended to reflect the most popular usage. See

separate articles for additional details.

- Piccolo clarinet - Very rare. Also known as Octave clarinet or Sopranino clarinet.About an octave higher

than the B flat clarinet.

- A flat piccolo clarinet

- Shackleton lists also obsolete instruments in C, B flat, and A.

- Soprano clarinet - The most familiar type of clarinet.

- E flat clarinet - Fairly common in America and western Europe; less common in eastern Europe.

Shackleton lists this and the D clarinet, along with obsolete instruments in G, F, and E

as sopranino clarinets, but this terminology is not commonly used.

- D clarinet - Rare in America and western Europe.

- C clarinet - Moderately rare.

- B flat clarinet - The most common type of clarinet.

- A clarinet - Standard orchestral instrument used alongside the B flat Soprano.

- G clarinet - Also called a "Turkish Clarinet". Primarily used in ethnic music.

- Shackleton lists also obsolete instruments in B and A flat. The latter and the clarinet in G often

occurred as clarinette d'amour in the mid-18th century.

- Basset clarinet - Essentially a soprano clarinet with a range extension to low C (written).

- A basset clarinet - Most common type.

- Basset clarinets in C, B flat, and G also exist.

- Basset horn - Alto-to-tenor range instrument with (usually) a smaller bore than the alto clarinet, and

a range extended to low (written) C.

- F basset horn - Most common type.

- Shackleton lists also basset horns in G and D from the 18th century.

- Alto clarinet - About half an octave lower than the B flat clarinet.

- E flat alto clarinet - Most common type.

- Bass clarinet - An octave below the B flat clarinet often with an extended low range.

- B flat bass clarinet - The standard bass.

- A bass clarinet - Obsolete.

- C bass clarinet - Obsolete.

- Contra-alto clarinet - An octave below the alto clarinet.

- EE flat contra-alto clarinet.

- Contrabass clarinet - An octave below the bass clarinet.

- BB flat contrabass clarinet.

Two larger types have been built on an experimental basis:

- EEE flat Octocontra-alto - An octave below the contra-alto clarinet. Only three have been built.

- BBB flat Octocontrabass - An octave below the contrabass clarinet. Only one was ever built, and is in

the personal collection of George Leblanc.

A contrabasset horn in F, an octave lower than the basset horn, has been mentioned in the literature.

History

The clarinet started life as a small instrument called the chalumeau. Not much is known about this instrument,

but it may have evolved from the recorder. The chalumeau had a similar reed to the modern clarinet, but lacked

the register key which extends the range to nearly four octaves, so it had a limited range of about one and a

half octaves. It also lacked certain chromatics. Like a recorder, it had eight finger holes, and usually had one

or two keys for extra notes.

In 1690, a German instrument maker named Johann Christoph Denner added a register key to the chalumeau and produced

the first clarinet. This instrument played well in the middle register with a loud, strident tone, so it was given

the name clarinetto meaning "little trumpet" (from clarino + -etto). Early clarinets did not

play well in the lower register, so chalumeaus continued to be made to play the low notes and these notes became

known as the chalumeau register. As clarinets improved, the chalumeau fell into disuse.

The original Denner clarinets had two keys, but various makers added more to get extra notes. The classical clarinet

of Mozart's day would probably have had eight finger holes and five keys.

Clarinets were soon accepted into orchestras. Later models had a mellower tone than the originals. Mozart (d. 1791)

liked the sound of the clarinet and wrote much music for it, and by the time of Beethoven (c. 1800-1820), the clarinet

was a standard fixture in the orchestra.

The next major development in the history of clarinet was the invention of the modern pad. Early clarinets covered

the tone holes with felt pads. Because these leaked air, the number of pads had to be kept to a minimum, so the

clarinet was severely restricted in what notes could be played with a good tone. In 1812, Ivan Mueller, a Russian-born

clarinetist and inventor, developed a new type of pad which was covered in leather or fish bladder. This was completely

airtight, so the number of keys could be increased enormously. He designed a new type of clarinet with seven finger

holes and thirteen keys. This allowed the clarinet to play in any key with near equal ease. Over the course of the

19th century, many enhancements were made to Mueller's clarinet, such as the Albert system and the Baermann system,

all keeping the same basic design. The Mueller clarinet and its derivatives were popular throughout the world.

The final development in the modern design of the clarinet was introduced by Hyacinthe Klose in 1839. He devised a

different arrangement of keys and finger holes which allow simpler fingering. It was inspired by the Boehm system

developed by Theobald Boehm, a flute maker who had invented the system for flutes. Klose was so impressed by Boehm's

invention that he named his own system for clarinets the Boehm system, although it is different from the one used on

flutes. This new system was slow to catch on because it meant the player had to relearn how to play the instrument.

Gradually, however, it became the standard and today the Boehm system is used everywhere in the world except Germany

and Austria. These countries still use a direct descendant of the Mueller clarinet known as the Oehler system clarinet.

Also, some contemporary Dixieland and Klezmer players continue to use Albert system clarinets, as the simpler fingering

system can allow for easier slurring of notes. At one time the reed was held on using string, but now the practice

exists primarily in Germany and Austria, where the warmer, thicker tone is preferred over that produced with

the ligatures that are more popular in the rest of the world.

References

- Pino, Dr. David The Clarinet and Clarinet Playing. Providence: Dover Pubns, 1998, 320 p.; ISBN 0486402703

- Nicholas Shackleton. "Clarinet", Grove Music Online, ed. L. Macy

This article is licensed under the GNU Free Document License

It uses material from the Wikipedia article - Clarinet

|