|

The violin is a bowed stringed musical instrument that has four strings tuned a perfect fifth apart. The range of the violin is from

the G just below middle C to the highest notes of the piano. It is the smallest and highest-tuned member of the violin family of string

instruments, which also includes the viola and cello. (A related bowed string instrument, the double bass, technically belongs to the similar

but distinct viol family.)

A violin is sometimes informally called a fiddle, no matter what sort of music is played on it. The words "violin" and "fiddle" come from the

same Middle Latin vitula, but "violin" came through the Romance languages, meaning small viola, and "fiddle" through Germanic

languages.

A person who plays violin is called a violinist or fiddler, and a person who makes or repairs them is called a luthier, or simply a violinmaker.

History of the violin

An intricately carved 17th century (believed 1665) so called 'King James' by Ralph Agutter, British Royal Family violin,

on display in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

The violin first emerged in northern Italy in the early 16th century. Most likely the first makers of violins borrowed from three different

types of current instruments: the rebec, in use since the 10th century (itself derived from the Arab rebab), the Renaissance fiddle,

and the lira da braccio. The Indian Ravanastron is also a predecessor of the violin. The earliest explicit description of the instrument,

including its tuning, was in the Epitome musical by Jambe de Fer, published in Lyon in 1556. By this time the violin had already begun

to spread throughout Europe.

It is said that the first real violin was built by Andrea Amati in the first half of the 16th century by order of the Medici family, who had

asked for an instrument that could be used by street musicians, but with the quality of a lute, which was a very popular instrument among the

noble in that time. The violin immediately became very popular, both among street musicians and the nobility, illustrated by the fact that the

French king Charles IX ordered Amati to build a whole orchestra in the second half of the 16th century.

The oldest surviving violin, dated inside, is the "Charles IX" by Andrea Amati, made in Cremona in 1564. "The Messiah" or "Le Messie"

(also known as the "Salabue") made by Antonio Stradivari in 1716 remains pristine, never having been used. It is now located in the Ashmolean

Museum of Oxford. The most famous violin makers, called luthiers, between the late 16th century and the 18th century included:

- Amati family of Italian violin makers, Andrea Amati (1500-1577), Antonio Amati (1540-1607), Hieronymous Amati I (1561-1630), Nicolo

Amati (1596-1684), Hieronymous Amati II (1649-1740)

- Guarneri family of Italian violin makers, Andrea Guarneri (1626-1698), Pietro of Mantua (1655-1720), Giuseppe Guarneri (Joseph filius

Andreae) (1666-1739), Pietro Guarneri (of Venice) (1695-1762), and Giuseppe (del Gesu) (1698-1744)

- Antonio Stradivari (1644-1737) of Cremona

- Jacob Stainer (1617-1683) of Absam in Tyrol

It is still believed, perhaps erroneously, that at the beginning of the 18th century, the violin was built in a way that can be expressed as

"perfect." It is commonly asserted that "Never since that time has a major improvement been made to the instrument", but changes have

occurred, particularly to do with the length and angle of the neck, as well as a heavier bass bar. The majority of old instruments have

undergone these modifications, and hence are in a significantly different state than when they left the hands of their makers, doubtless

with differences in sound and response.

Nevertheless, instruments of approximately 300 years of age, especially those made by Stradivari and Guarneri del Gesu, are the most sought

after instruments (for both collectors and performers). In addition to the skill and reputation of the maker, an instrument's age can also

influence both price and quality.

Violin construction and mechanics

The Construction of a Violin

Construction

A violin typically consists of a spruce top, maple ribs and back, two endblocks, a neck, a bridge, a soundpost, four strings, and various

fittings, optionally including a chinrest, which may attach directly over, or to the left of, the tailpiece. A distinctive feature of a violin

body is its "hourglass" shape and the arching of its top and back. The hourglass shape comprises an upper bout, a lower bout, and two concave

C-bouts at the "waist," providing clearance for the bow.

The voice of a violin depends on its shape, the wood it is made from, the "graduation" (the thickness profile) of both the top and back, and

the varnish which coats its outside surface. The varnish and especially the wood continue to improve with age, making the fixed supply of old

violins much sought-after. Loose parts or open seams may cause buzzes and should be professionally attended to; in particular, no adhesive

other than animal hide glue should ever be used on a violin. A well-tended violin can outlive many generations of players, so it is wise to

take a curatorial view when caring for a violin.

The purfling running around the edge of the spruce top is said to give some resistance to cracks originating at the edge. It is also claimed

to allow the top to flex more independently of the rib structure. Painted-on faux purfling on the top is usually a sign of an inferior instrument.

Ideally the top is glued on with slightly diluted hide glue, to make future removal possible. The back and ribs are typically made of maple, most

often with a matching striped figure, called "flame."

The neck is usually maple with a flamed figure compatible with that of the ribs and back. It carries the fingerboard, typically made of ebony,

but often some other wood stained or painted black. Ebony is considered the preferred material because of its hardness, beauty, and superior

resistance to wear. The maple neck alone is not strong enough to support the tension of the strings without distorting, relying for that strength

on its lamination with the fingerboard. For this reason, if a fingerboard comes loose (it happens) it is vital to slacken the strings immediately.

The shape of the neck and fingerboard affect how easily the violin may be played. Fingerboards are dressed to a particular transverse curve, and

have a small lengthwise "scoop," or concavity, slightly more pronounced on the lower strings, especially when meant for gut or synthetic strings.

Some old violins (and some made to appear old) have a grafted scroll, or a seam between the pegbox and neck itself. Many authentic old instruments

have had their necks reset to a slightly increased angle, and lengthened by about a centimeter. The neck graft allows the original scroll to be

kept with a Baroque violin when bringing its neck to conformance with modern standard.

Bridge blank and finished bridge

The bridge is a carefully carved piece of maple, having several purposes: its top curve holds the strings at the proper height from the fingerboard

in an arc allowing each to be sounded separately by the bow. It also transmits the vibrations of the strings to the body of the violin. The sound

post, or "soul post", fits precisely between the back and top, and may be moved slightly when adjusting the tone of the instrument.

The tailpiece anchors the strings to the lower bout of the violin by means of the tailgut, which loops around the endpin, which fits into a

tapered hole in the bottom block. Very often the E string will have a fine tuning lever worked by a small screw turned by the fingers. Fine

tuners may also be applied to the other strings, and are sometimes built in to the tailpiece.

At the scroll end, the strings wind around the tuning pegs in the pegbox. Strings usually have a colored "silk" wrapping at both ends, for

identification and to provide friction against the pegs. The tapered pegs allow friction to be increased or decreased by the player applying

appropriate pressure along the axis of the peg while turning it. Various brands of peg compound or peg dope help keep the pegs from sticking

or slipping.

Violin and bow

Strings

Strings were first made of sheep gut, stretched, dried and twisted. Modern strings may be solid steel, stranded steel, or various synthetic

materials, wound with various metals.

Violinists carry replacement strings with their instruments to have one available in case a string breaks. A teacher can advise students how

often to change strings, as it depends on how much and how hard one plays. Apart from obvious things, such as the winding of a string coming

undone from wear, a player will generally change a string when it no longer plays "true", with a negative effect on intonation.

Pitch range

The compass of the violin is from the G below the middle C to the top octave of the modern piano.

Acoustics

The arched shape, the thickness of the wood, and its physical qualities govern the sound of a violin. Patterns of the nodes (places of no movement)

made by sand or glitter sprinkled on the plates with the plate vibrated at certain frequencies, called "Chladni patterns", are occasionally used

by luthiers to verify their work before assembling the instrument.

Sizes

Children learning the violin often use fractional sized violins, 3/4, 1/2, 1/4, 1/8, 1/10, and 1/16. Occasionally, even a 1/32 sized instrument

is used.

The body length (not including the neck) of a 'full-size' or 4/4 violin is about 14 inches (35 cm) or smaller in some models of the 17th century.

A 3/4 violin is 13 inches (33 cm), and a 1/2 size is 12 inches (30 cm). Viola size is specified as body length in inches rather than fractional

sizes. A 'full-size' viola averages 16 inches (40 cm).

When determining the violin size appropriate for a child, a general rule is to have the child hold the instrument against the neck, and reach

out past the end of the scroll. Some teachers feel that students can handle a size if they are able to reach around the end of the scroll and

see the tips of the fingers, while others recommend smaller sizes as safer, preferring to have the scroll fall short of the student's wrist.

Tuning

Scroll and pegbox, correctly strung

The pitches of open strings on a violin

Violins are tuned by turning the pegs in the pegbox under the scroll, or by turning the fine tuner screws at the tailpiece. A violin

always has pegs, but fine tuners (also called fine adjusters) are optional. These permit the string tension to be adjusted in very

small amounts much more easily than by using the pegs. Fine tuners work by turning a small metal screw, which moves a lever that is attached

to the end of the string. Fine tuners are usually recommended for younger players, fractional-sized instruments, those using high tension or

metal strings, or beginners. Fine tuners are most useful with solid metal strings; since they do not stretch as much as synthetics, solid-core

strings can be touchy to tune with pegs alone. Fine tuners are not useful when using gut strings; since these strings are more "stretchy", the

tuners lack enough range of travel to make a significant pitch difference, and the sharp corners on the prongs may cause the string to break

where the string passes over them. Most players use a fine tuner on the E-string even if the other strings are not so equipped.

The A string is first tuned to a standard pitch (usually 440 Hz) or to another instrument. (When playing with a fixed-pitch instrument such

as a piano or accordion, the violin must tune accordingly.) The other strings are then tuned to each other, starting with the tuned A string, in

intervals of perfect fifths by bowing them in pairs. Sometimes, a minutely higher pitch is used to tune for solo playing to give the instrument

a brighter sound. After tuning, experienced players make sure that the bridge is standing straight and centered between the inner nicks of the

f holes, since bridges are free to move about, being held in place only by the tension of the strings.

The tuning G-D-A-E is used for the great majority of all violin music. However, any number of other tunings are occasionally employed (for

example, tuning the G string up to A), both in classical music, where the technique is known as scordatura, and in some folk styles

where it is called "cross-tuning." One famous example of scordatura in classical music is Saint-Saens' Danse Macabre, where the solo violin's

E string is tuned down to E flat to give the part an eerie dissonant sound.

Some electric violins have five, six, or even seven strings, others have the usual four. Usually the extra strings go lower, to C, F, and B

flat. If the instrument's playing length, or string length from nut to bridge, is equal to a violin's (a bit less than 13 inches, or 330 mm,)

it may be properly termed a violin. Acoustic 5-string instruments exist, with a scale length closer to that of a viola's; they are commonly

called violas.

Bows

Bow frogs, top to bottom: violin, viola, cello

A violin is usually played using a bow consisting of a stick with a ribbon of horsehair strung between the tip and frog (or nut, or heel) at

opposite ends. A typical violin bow may be 29 inches (74.5 cm) overall, and weigh about 2 oz. (60 g). Viola bows may be about 3/16" (5 mm)

shorter and 1/3 oz. (10 g) heavier.

At the frog end, a screw adjuster tightens or loosens the hair. Just forward of the frog, a leather thumb cushion and winding protect the stick

and provide grip for the player's hand. The winding may be wire, silk, or whalebone (now imitated by alternating strips of yellow and black

plastic.) Some student bows (particularly the ones made of solid fiberglass) substitute a plastic sleeve for grip and winding.

The hair of the bow traditionally comes from the tail of a "white" (technically, a grey) male horse, although some cheaper bows use synthetic

fiber. Occasional rubbing with rosin makes the hair grip the strings intermittently, causing them to vibrate. The stick is traditionally made

of pernambuco or the less expensive brazilwood, although some student bows are made of fiberglass. Recent innovations have allowed carbon-fiber

to be used as a material for the stick at all levels of craftsmanship.

Playing the violin

The standard way of holding the violin is under the chin and supported by the left shoulder, often assisted by a shoulder rest. (However, some

cultures vary in this practice; for instance, Indian (Carnatic and Hindustani) violinists play seated on the floor and rest the scroll of the

instrument on the side of their foot.) The strings may be sounded either by plucking them (pizzicato) or by drawing the hair of the bow

across them (arco). The left hand regulates the sounding length of the string by stopping it against the fingerboard with the fingertips,

producing different pitches.

Left hand and pitch production

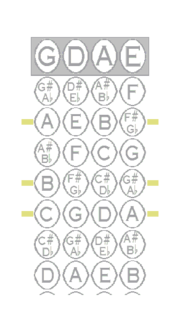

First Position Fingerings

As placement of the left hand fingers on the strings is not aided by frets; players must finger the string at the right spot by skill alone,

or they will sound out of tune. Good intonation comes from lots of practice.

Beginners often rely on tapes on the finger board in several places for proper left hand finger placement, but quickly abandon the tapes as

they advance. Another commonly-used marking technique uses dots of typists correction fluid on the fingerboard, which wear off in a few weeks

of regular practice.

The fingers are conventionally numbered 1 (index) through 4 (little finger). Especially in instructional editions of violin music, numbers

over the notes may indicate which finger to use, with "O" indicating "open" string. The chart to the right shows the arrangement of notes

reachable in first position.

Left hand finger placement is a matter for the ears and hand, not the eyes. That is, finger placement has strong aural and tactile/kinesthetic

components; visual references are only marginally useful. Note also (not shown on this chart) that the spacing between note positions becomes

closer as the fingers move up (in pitch) from the nut. The yellow bars on the sides of the chart represent three of the usual tape placements

for beginners, at 1st, high 2nd, and 3d fingers.

Positions

The placement of the left hand on the fingerboard is characterized by "positions". First position, where most beginners start (although some

methods start in third position), is the most commonly used position in string music. The lowest note available in this position in standard

tuning is an open G; the highest note in first position is played with the fourth finger on the E-string, sounding a B, or reaching up a half

step (also known as the "extended fourth finger") to the C two octaves above middle C.

Moving the hand up the neck, so the first finger takes the place of the second finger, brings the player into second position. Letting

the first finger take the first-position place of the third finger brings the player to third position, and so on. The upper limit of

the violin's range is largely determined by the skill of the player, who may easily play more than two octaves on a single string, and four

octaves on the instrument as a whole. The lowest position on a violin is half-position, where the first finger is very close to the nut, this

position is usually only used in complex music or music with many flatted notes.

Violinists usually change positions in a first finger to third finger pattern; where the first finger is moved to the place of the third finger

(ie. on the A string moved from B to D) The most logical and common shifting positions are first position to third position, and then to fifth

position if necessary.

The same note will sound substantially different depending on what string is used to play it. Sometimes the composer or arranger will specify

the string to be used in order to achieve the desired tone quality; this is indicated in the music by the marking, for example, sul G,

meaning to play on the G string. Playing high up on the G and D strings in particular gives a distinctively strained quality to the sound.

Otherwise, moving into different positions is usually done for tactical reasons, for reaching higher notes or avoiding string crossings.

Open strings

A special timbre results from bowing a note on an open string, or without touching its string with a finger. Open string notes (G, D, A, E)

have a very distinct sound resulting from lack of contact by the finger. Other than low G (which can be played in no other way), open strings are

usually selected for special effects. In classical music, an open string is sometimes considered to make a rather harsh sound and, in most cases,

should be avoided (this is especially true of the E string which has a very metallic tone).

Playing an open string simultaneously with a stopped note on an adjacent string produces a bagpipe-like drone, often used by composers in

imitation of folk music. Sometimes the two notes are identical (for instance, playing a fingered A on the D string against the open A string),

giving a ringing sort of "fiddling" sound.

Double stops and drones

Double stopping is when two separate strings are stopped by the fingers, and bowed simultaneously, producing a part of a chord. Sometimes moving

to a higher position is necessary for the left hand to be able to reach both notes at once. Sounding an open string alongside a fingered note is

another way to get a partial chord. While sometimes also called a double stop, it is more properly called a drone, as the drone note may be

sustained for a passage of different notes played on the adjacent string. Three or four notes can also be played at one time (triple and quadruple

stops, respectively), and, according to the style of music, the notes might all be played simultaneously or might be played as two successive

double stops, favoring the higher notes.

Vibrato

Vibrato is a technique of the left hand and arm in which the pitch of a note varies in a pulsating rhythm. While various parts of the hand or

arm may be involved in the motion, the end result is a movement of the fingertip bringing about a slight change in vibrating string length.

Violinists oscillate backwards, or lower in pitch from the actual note when using vibrato, since perception favors the highest pitch in a varying

sound. Vibrato does little, if anything, to disguise an out-of-tune note: in other words, vibrato is a poor substitute for good intonation. Music

students are taught that unless otherwise marked in music, vibrato is assumed or even mandatory. This can be an obstacle to a classically-trained

violinist wishing to play in a style that uses little or no vibrato at all, such as baroque music played in period style and many traditional

fiddling styles.

The "when" and "what for" of violin vibrato are artistic matters of style and taste. In acoustical terms, the interest that vibrato adds to

the sound has to do with the way that the overtone mix (or tone color, or timbre) and the directional pattern of sound projection change with

changes in pitch. By "pointing" the sound at different parts of the room in a rhythmic way, vibrato adds a "shimmer" or "liveliness" to the

sound of a well-made violin.

Harmonics

Lightly touching the string with a fingertip at a harmonic node while bowing close to the bridge can create harmonics. Instead of the

normal solid tone a wispy-sounding overtone note of a higher pitch is heard. Each node is at an integer division of the string, for example

half-way or one-third along the length of the string. A responsive instrument will sound numerous possible harmonic nodes along the length of

the string.

Harmonics are marked in music with a little circle above the note that determines the pitch of the harmonic. There are two types of harmonics:

natural harmonics and artificial harmonics (also known as false harmonics).

Natural harmonics are played on an open string. The pitch of the open string is called the fundamental frequency. Harmonics are also called

overtones. They occur at whole-number multiples of the fundamental, which is called the first harmonic. The second harmonic is the

first overtone, the third harmonic is the second overtone, and so on. The second harmonic is in the middle of the string and sounds an octave

higher than the string's pitch. The third harmonic breaks the string into thirds, and the fourth harmonic breaks the string into fourths. The

sound of the second harmonic is the clearest of them all, because it is a common node with all the succeeding even-numbered harmonics (4th,

6th, etc.). The third harmonic (and succeeding odd-numbered harmonics) are harder to play because they break the string into three (or other

odd-numbered parts) and don't share as many nodes with other harmonics.

Artificial harmonics are more difficult to produce than natural harmonics, as they involve both stopping the string and playing a harmonic on

the stopped note. Using the "octave frame"-the normal distance between the first and fourth fingers in any given position-with the fourth finger

just touching the string a fourth higher than the stopped note produces the fourth harmonic, two octaves above the stopped note. Finger placement

and pressure, as well as bow speed, pressure, and sounding point are all essential in getting the desired harmonic to sound. And to add to the

challenge, in passages with different notes played as false harmonics, the distance between stopping finger and harmonic finger must constantly

change.

The "harmonic finger" can also touch at a major third above the pressed note, or a fifth higher. These harmonics are less commonly used; in the

case of the major third, the harmonic does not speak as readily; in the case of the fifth, the stretch is greater than is comfortable for many

violinists.

Elaborate passages in artificial harmonics can be found in virtuoso violin literature, especially of the 19th and early 20th centuries. (One

notable example is an entire section of Vittorio Monti's Csardas.)

Right Hand & Tone Colour

The right arm, hand, and bow are responsible for tone quality, rhythm, dynamics, articulation, and certain (but not all) changes in timbre.

Bowing techniques

The most essential part of bowing technique is the bow grip. It is usually with the thumb bent in the small area between the frog and the

winding of the bow. The other fingers are spread somewhat evenly across the top part of the bow.

The violin produces louder notes with greater bow speed or more weight on the string. The two methods are not equivalent, because they produce

different timbres; pressing down on the string tends to produce a harsher, more intense sound.

The sounding point where the bow intersects the string also influences timbre. Playing close to the bridge (sul ponticello) gives a

more intense sound than usual, emphasizing the higher harmonics; and playing with the bow over the end of the fingerboard (sul tasto)

makes for a delicate, ethereal sound, emphasizing the fundamental frequency. Dr. Suzuki referred to the sounding point as the "Kreisler highway";

one may think of different sounding points as "lanes" in the highway.

Various methods of 'attack' with the bow produce different articulations. There are many bowing techniques that allow for every range of playing

style and many teachers, players, and orchestras spend a lot of time developing techniques and creating a unified technique within the group.

Pizzicato

A note marked pizz. (abbreviation for pizzicato) in the written music is to be played by plucking the string with a finger of the

right hand rather than by bowing. (The index finger is most commonly used here.) Sometimes in virtuoso solo music where the bow hand is occupied

(or for show-off effect), left-hand pizzicato will be indicated by a "+" (plus sign) below or above the note. In left-hand pizzicato, two

fingers are put on the string; one (usually the index or middle finger) is put on the correct note, and the other (usually the ring finger or

little finger) is put above the note. The higher finger then plucks the string while the lower one stays on, thus producing the correct pitch.

Col legno

A marking of col legno (Italian for "with the wood") in the written music calls for striking the string(s) with the stick of the bow,

rather than by drawing the hair of the bow across the strings. This bowing technique is somewhat rarely used, and results in a muted percussive

sound. The eerie quality of a violin section playing col legno is exploited in some symphonic pieces, notably the "witches' dance" of

the last movement of Berlioz' Symphonie Fantastique. Some violinists, however, object to this style of playing as it can damage the finish and

impair the value of a fine bow.

Mute

Attaching a small metal or rubber device called a "mute" to the bridge of the violin gives a more mellow tone, with fewer audible overtones.

Parts to be played muted are marked con sord., for the Italian sordino, mute. (The instruction to play normally, without the

mute, is senza sord.) There are also much larger metal, rubber, or wooden mutes available. These are known as "practice mutes" or

"hotel mutes". Such mutes are generally not used in performance, but are used to deaden the sound of the violin in practice areas such as

hotel rooms. Some composers have used practice mutes for special effect, for example at the end of Luciano Berio's Sequenza VIII for

solo violin, and in the third to fifth movements of Dmitri Shostakovich's String Quartet No. 8.

Musical styles

Classical music

Since the Baroque era the violin has been one of the most important of all instruments in classical music, for several reasons. The tone of

the violin stands out above other instruments, making it appropriate for playing a melody line. In the hands of a good player, the violin is

extremely agile, and can execute rapid and difficult sequences of notes.

The violin is also considered a very expressive instrument, which is often felt to approximate the human voice. This may be due to the possibility

of vibrato and of slight expressive adjustments in pitch and timbre. Many leading composers have contributed to the violin concerto and violin

sonata repertories.

Violins make up a large part of an orchestra, and are usually divided into two sections, known as the first and second violins. Composers often

assign the melody to the first violins, while second violins play harmony, accompaniment patterns or the melody an octave lower than the first

violins. A string quartet similarly has parts for first and second violins, as well as a viola part, and a bass instrument, such as the cello

or, rarely, the bass.

Jazz

The violin is used as a solo instrument in jazz, though it is a relative rarity in this genre; compared to other instruments, such as saxophone,

trumpet, piano and guitar, the violin appears fairly infrequently. It is, however, very well suited to jazz playing, and many players have

exploited its qualities well.

The earliest references to jazz performance using the violin as a solo instrument are documented during the first decades of the 20th century.

The first great jazz violinist was Joe Venuti who is best known for his work with guitarist Eddie Lang during the 1920s. Since that time there

have been many superb improvising violinists including Stephane Grappelli, Stuff Smith, Ray Perry, Ray Nance, Claude "Fiddler" Williams, Leroy

Jenkins, Billy Bang, Mat Maneri, Malcolm Goldstein. Other notable jazz violinists are Regina Carter, and Jean-Luc Ponty.

Violins also appear in ensembles supplying orchestral backgrounds to many jazz recordings.

Popular music

While the violin has had very little usage in rock music compared to its brethren the guitar and bass guitar, it is increasingly being absorbed

into mainstream pop with artists like Vanessa Mae, Bond, Linda Brava, Miri Ben-Ari, The Corrs, Nigel Kennedy, Yellowcard, Dave Matthews Band

with Boyd Tinsley, Arcade Fire, Jean-Luc Ponty, Camper Van Beethoven, and The Who (in the coda of their 1971 song Baba O'Riley). Independent

artists such as Final Fantasy and Andrew Bird have also spurred increased interest in the instrument. It has also seen usage in the post-rock

genre by bands like Broken Social Scene and Hope of the States.

The hugely popular Motown recordings of the 60's and 70's relied heavily on strings as part of their trademark texture. Earlier genres of pop

music, at least those separate from the Rock 'n' Roll movement, tended to make use of fairly traditional orchestras, sometimes large ones;

examples include the American "Crooners" such as Bing Crosby.

Up to the 1970s, most types of popular music used bowed strings, but the rise of electronically created music in the 1980s saw a decline in

their use, as synthesized string sections took their place. Since the end of the 20th century, real strings have began making a comeback in

pop music.

Indian and Arabic pop music is filled with the sound of violins, both soloists and ensembles.

Some folk/viking metal bands use the violin in their songs (i.e. Thyrfing), and some even have a permanent violinist (i.e. Asmegin).

One of the best-selling bands of the 1990's, the Corrs, relied heavily on the skills of violinist Sharon Corr. The violin was intimately integrated

with the Irish tin whistle, the Irish hand drum (bodhran), as well as being used as intro and outro of many of their Celtic-flavored pop-rock songs.

Indian classical music

The violin is a very important part of South Indian classical music (Carnatic music). It is believed to have been introduced to the South Indian

tradition by Baluswamy Dikshitar. Though primarily used as an accompaniment instrument, the violin has gained prominence as a solo instrument in

the contemporary Indian music scene.

The violin is also a principal instrument for South Indian film music. Film composers Ilayaraaja and A. R. Rahman have used the violin very

effectively in this genre. V. S. Narasimhan is among the undisputed violin wizards in the South Indian film industry, with many hits in the

film world.

There are a few instrumentalists, such as V. S. Narasimhan, who have complete mastery over their instrument, as well as a deep knowledge of

both Indian and Western classical traditions.

Folk music and fiddling

Like many other instruments of classical music, the violin descends from remote ancestors that were used for folk music. Following a stage of

intensive development in the late Renaissance, largely in Italy, the violin had improved (in volume, tone, and agility), to the point that it

not only became a very important instrument in art music, but proved highly appealing to folk musicians as well, ultimately spreading very

widely, sometimes displacing earlier bowed instruments. Ethnomusicologists have observed its widespread use in Europe, Asia, and the Americas.

In many traditions of folk music, the tunes are not written but are memorized by successive generations of musicians and passed on in both

informal and formal contexts.

Fiddle

When played as a folk instrument, the violin is ordinarily referred to in English as a fiddle.

One very slight difference between "fiddles" and ordinary violins may be seen in American (e.g., bluegrass and old-time music) fiddling: in these

styles, the bridge is often shaved down so that it is less curved. This makes it easier to play double stops, and often makes triple stops possible,

allowing one to play chords.

MIDI

The sound of a real violin can be simulated electronically with the MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface) system, using electronic

synthesis. Under MIDI, all instruments are assigned a number; a single violin played arco is instrument #41, where the numbering begins

from #1. Though general MIDI does not allow for distinction between up bows and down bows, it is possible to differentiate between staccato

and legato by adjusting note durations, which most notation software capable of outputting MIDI can handle. General MIDI also provides for

regular pizzicato but not left-hand pizzicato, but in any case, under MIDI, pizzicato is at most an approximation of the actual sound.

Further reading

Books:

- The Contemporary Violin: ExtENDed Performance Techniques, by Patricia and Allen Strange, ISBN 0520224094

- The Fiddle Book, by Marion Thede, (1970), Oak Plublications. ISBN 0825601452

- Latin Violin, by Sam Bardfeld, ISBN 0962846775

This article is licensed under the GNU Free Document License

It uses material from the Wikipedia article - Violin

|